Creative Writing

Creative Writing

Leave Classwork in the Classroom

Have you ever begun to read a work of fiction and almost immediately had the thought, Oh! This author has taken a class on creative writing? I find that this usually occurs to me when I’m reading a narrative passage with an unnecessary amount of description that seems to make a point of including all five senses: taste, touch, smell, sight, and sound. Take the following example:

Robert stepped out of the freezing cold of the ice cream parlor into warm sunshine and felt his ears begin to thaw. The springtime fragrance of jasmine pleasantly tickled his nose as he sauntered down the sidewalk, noting the hardness of the concrete beneath his shoes. As he walked on, he took a lick of the pale green ice cream stuffed into the waffled cone clutched tightly in his hand. Already the frozen concoction was beginning to drip down the cone. He felt a sticky, gelatinous stream begin to slide down his wrist and licked it, tasting the salt of his sweat mixed in with the sweetness of sugar and cream. He licked his lips and then took a quick bite of the ice cream, wincing at the cold on his teeth even while enjoying the crunch of a pistachio nut between them.

The sound of a small plane engine droning overhead caught his attention, and he looked up between the sunlit leaves of an overhanging tree to get a glimpse of the plane. It was a Cessna, painted blue, and it was towing a long white sign with large black letters behind it. In an effort to get a better look at the sign, Robert stepped out from under the tree and looked up to read: Tammy, will you marry me?

Filing this away in his head as one more possible approach to making a proposal—if he should ever be so lucky as to get another girlfriend now that Sheila with her pixie blond hair and taunting, painted-on eyebrows had dumped him—Robert turned the corner, still looking up into the shimmering blue sky, and bumped right into a leggy young woman with big brown eyes and long, wavy red hair. Diverting his attention downward, he grimaced upon noticing that his ice cream cone was now crushed into the front of her white, lacy, voluptuously filled-out blouse.

Without knowing more about the story, we assume that the point of this scene is that Robert meets the girl with the long, wavy red hair by accidentally walking into her and crushing his ice cream cone between them, leaving a gooey mess on the front of her blouse. So it’s fine to indicate that he is walking down the sidewalk on a nice, sunny day with an ice cream cone, notices the sign being pulled by a plane overhead, takes note of this marriage proposal method for future reference, has his brief thought about the former girlfriend Sheila (leaving out her hair and eyebrows), and then bumps into the red-haired young woman, spilling ice cream onto her clothes.

But do we really need to know that he notices the hardness of the concrete sidewalk beneath his shoes (unless this is to indicate that his shoe soles have worn thin and that he is too poor to replace them, which would need to be more specifically stated) or that he licks ice cream off his wrist and enjoys the crunch of a nut between his teeth or that the plane pulling the sign is a blue Cessna? I think not.

Including more than sight, or even sight and sound, in your descriptions can be a good thing, but don’t go crazy trying to include all five senses every time you need a bit of description to bring the reader into the scene. When it comes to description, less is often more. Save all that expansive, precise detail for when you really need it—like when your protagonist is fleeing the villain through the woods and every sense of the protagonist is on high alert to help zerm to escape.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be a matter of life and death for you to want to use “real time” in your fiction. If you would like to see how one highly successful author uses description to create a sense of real time in a most dramatic way, I recommend you read Tom Wolfe’s A Man in Full, which includes several excellent examples.

In the meantime, keep your creative writing lesson assignments in a notebook to view at your leisure and keep only the overall important idea behind those lessons in your forebrain while doing the serious work of writing for the real world. Your readers will thank you.

© 2016 Ann Henry, all rights reserved.

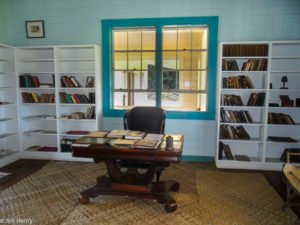

Photo: Whose Idea Was Homework, Anyway? © 2016 Ann Henry, all rights reserved.