Creative Writing

Creative Writing

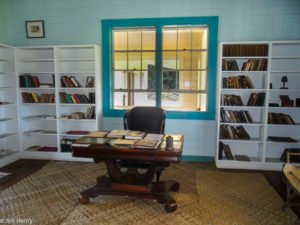

Enhance Your Story with Setting

When composing your story, don’t neglect the setting. Is it warm or cold? Spring or fall? Dawn or midnight? Does your story take place in an urban setting or on a rural farm? Are desert sands blowing or are ocean waves crashing? Or is the morning air at the beach warm and humid on a gentle breeze as it wafts in off a summer sea, bringing with it the smell of seaweed and the raucous caws of gulls?

When we speak of setting in the literary world, we mean time and place.

The time may be very general as in “prehistoric times” or “future times,” or it may be extremely specific as in “exactly three seconds before midnight on April 15, 2017.” The time of most stories falls somewhere between these two extremes—a twelfth-century winter afternoon; a morning in 1863; nine o’clock on a contemporary winter’s night; an eighteenth-century March day; a fourth watch in the 23rd Century.

As you can see, these temporal descriptions give us some idea about the story’s context but not nearly enough for us to feel at home there. For that, we need the second element of setting: place.

Again, place may be simply generic—a pine forest; a tropical isle; an Italian restaurant—or quite specific: the Oval Office of the White House, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C.

These examples of place may ground us a bit better than the time examples did, but still we are not confident of our surroundings until we put the two together.

See how much more you feel immersed in the description when you have both time and place: a twelfth-century Danish castle; the porch of a Vicksburg, Mississippi, antebellum home on a summer morning in 1863; nine o’clock at night on a current-day street corner in wintertime Chicago; an eighteenth-century March day in Dublin, Ireland; or the fourth watch on the bridge of a starship in the 23rd Century.

Once you have the basic time and place needed to convincingly convey your tale, fill in with details as needed to further support and enhance your story. If your voyaging yacht is caught in a gale, describe the time—midnight watch in mid-November, current year; the location—Atlantic Ocean, 200 miles northwest of Bermuda; the weather—northeasterly winds at 40 knots with lashing rain; lunar condition—moonless; sea conditions—22-foot seas with every fourth wave breaking over the stern; what sails, if any, are up; course direction, and so on.

If your story is a short story, it may well take place in a single room. If, on the other hand, it is a novella or novel, it may include many different times and locations. Give each the attention it deserves in relation to its importance in the tale so as to pull the reader more firmly into the story as the setting influences the plot and characters and, if appropriate, reflects the theme.

© 2017 Ann Henry, all rights reserved.

Photo: Chillin’ Out © 2017 James Henry, all rights reserved.